Open Letter to Supervisors Davis and Fanning — A Public Message to the Citizens of Santa Cruz County, Arizona

Subtitle: Transparency and accountability form the cornerstone of public trust. These principles are more important than ever. Rev 1/28/26

Chapter 17. This eBook will be released in chapters before being compiled into a complete volume.

January 8, 2026 — By John Brakey, Director of AUDIT USA

A documented investigative public accountability report, presented as an open letter and public record.

🎧 Podcast/Video: Read, Watch, or Listen

Open Letter to Supervisors Davis and Fanning — Public Message to the Citizens of Santa Cruz Co, AZ:

This investigative public accountability report documents longstanding structural failures in oversight, transparency, and election administration in Santa Cruz County, Arizona. Drawing on court records, Arizona statutes, and firsthand observation, it traces a pattern in which lawful public-records requests and election oversight were met with resistance, intimidation, and retaliatory litigation.

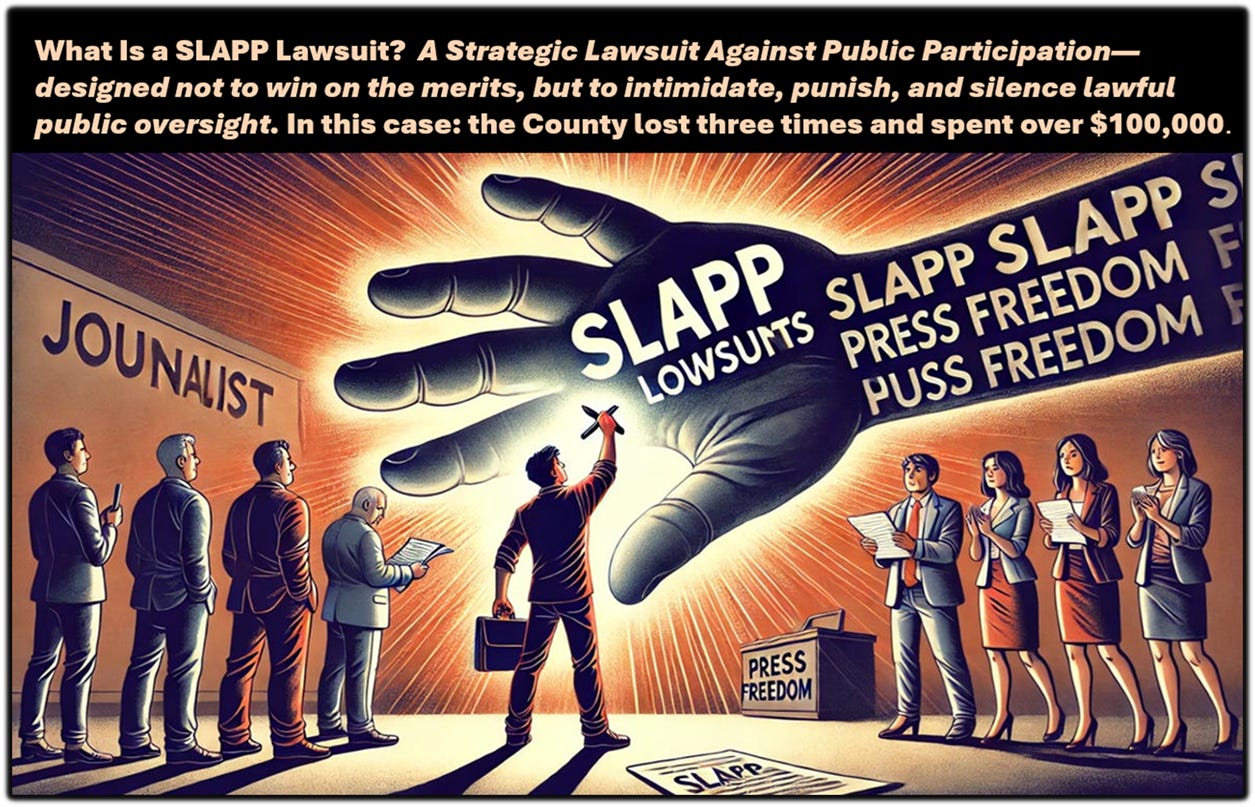

The report centers on a lawsuit filed by Santa Cruz County against a citizen organization for requesting standard election records—a case the County lost three times in court and is now defending before the Arizona Supreme Court. It demonstrates that voter privacy and public verification are not opposing principles, and that transparency mechanisms such as Cast Vote Records and public chain-of-custody procedures strengthen both voter protection and public trust.

The failures documented are structural rather than partisan and predate current county leadership. The report concludes by proposing a lawful, permanent Transparency & Elections Oversight Commission as a path forward to restore accountability and rebuild public confidence.

How to Read This Report

This is a long-form investigative public accountability report. It is designed to be read in sections.

You do not need to read it all at once.

Start here, based on your interest:

Want the big picture?

Read the Executive Summary and Why This Matters TodayInterested in elections and public records?

Read Parts I–V and Part X (The SLAPP Lawsuit)Concerned about election-night conduct and intimidation?

Read Parts VII–IXLooking for solutions, not just problems?

Skip ahead to Part XII — A Path ForwardFinal Chapter: A Reasonable Path Forward — the Consequences of Refusal Skip ahead to Read Part XIV

This report is fully documented and written as a public record. Sections stand on their own and may be read independently.

To Supervisors Davis and Fanning

You both stepped into public service during one of the most difficult chapters in Santa Cruz County’s history. That decision deserves recognition.

Intent matters. Character matters. Service matters.

Both of you answered the call to serve.

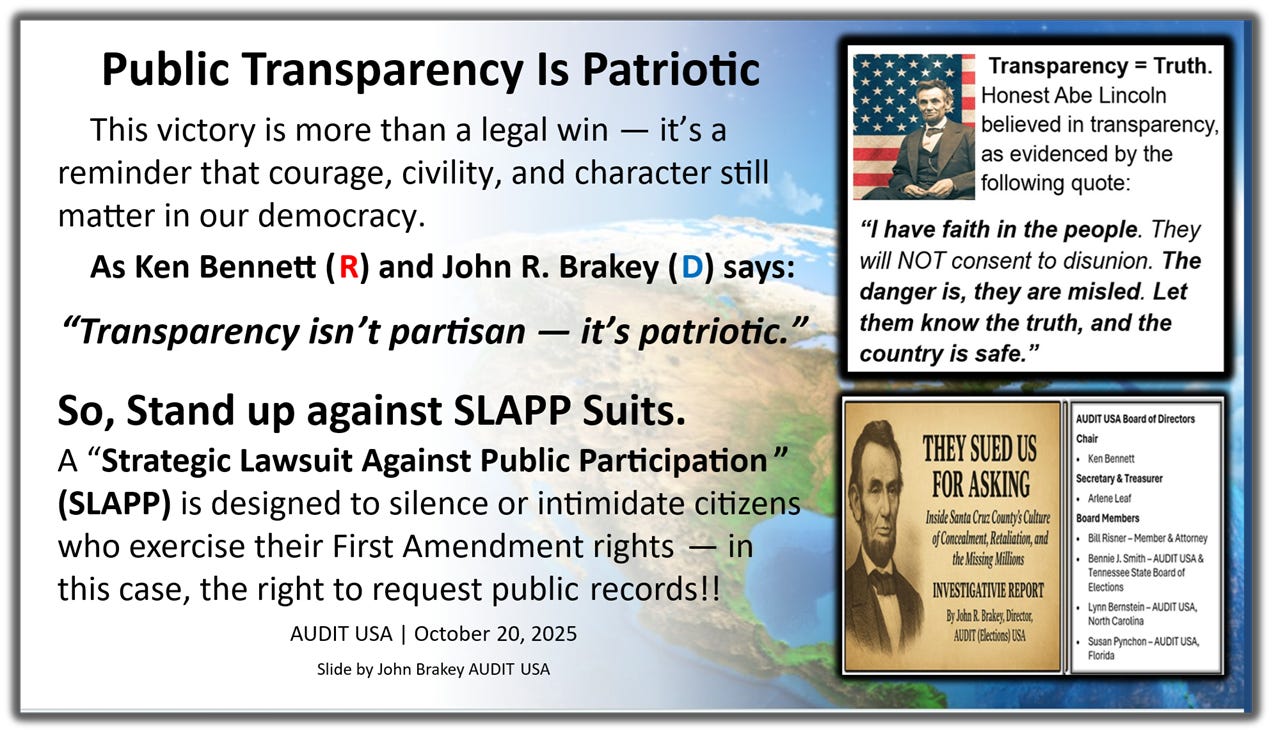

Former Arizona Secretary of State Ken Bennett and I have worked across this state for more than two decades. We know how rare it is for local leaders to say “yes” to oversight and accountability.

You will deserve credit when you commit to:

making public records easier to request,

listening to citizens rather than dismissing them as troublemakers, and

recognizing that distrust is not hostility—it is often a request for proof.

This letter is written in that spirit.

What the Lawsuit Revealed

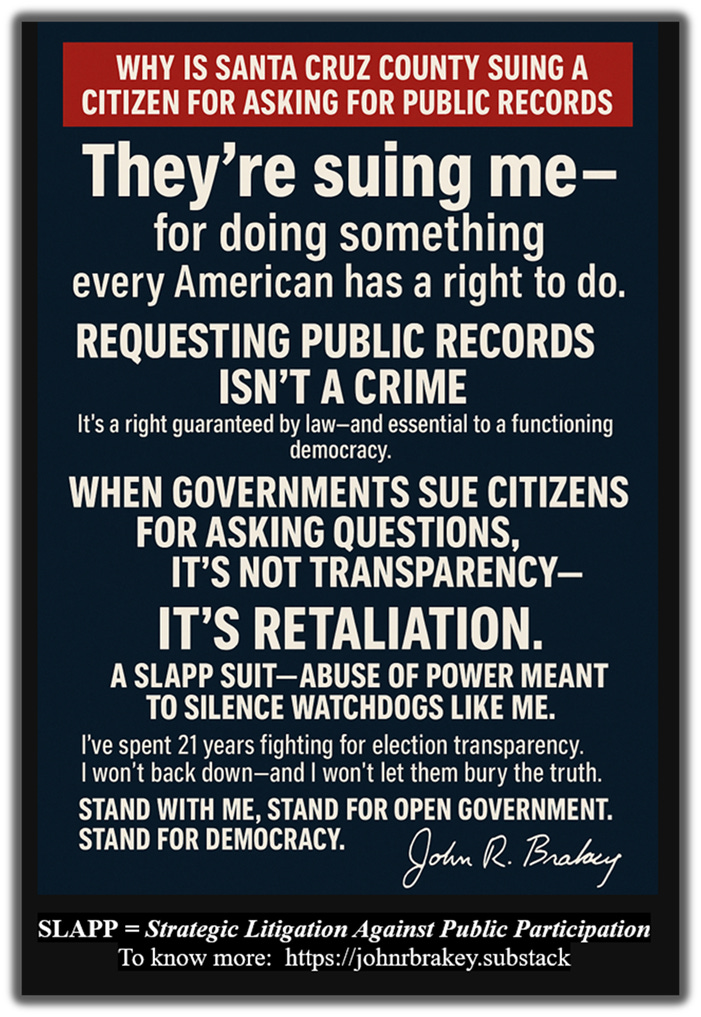

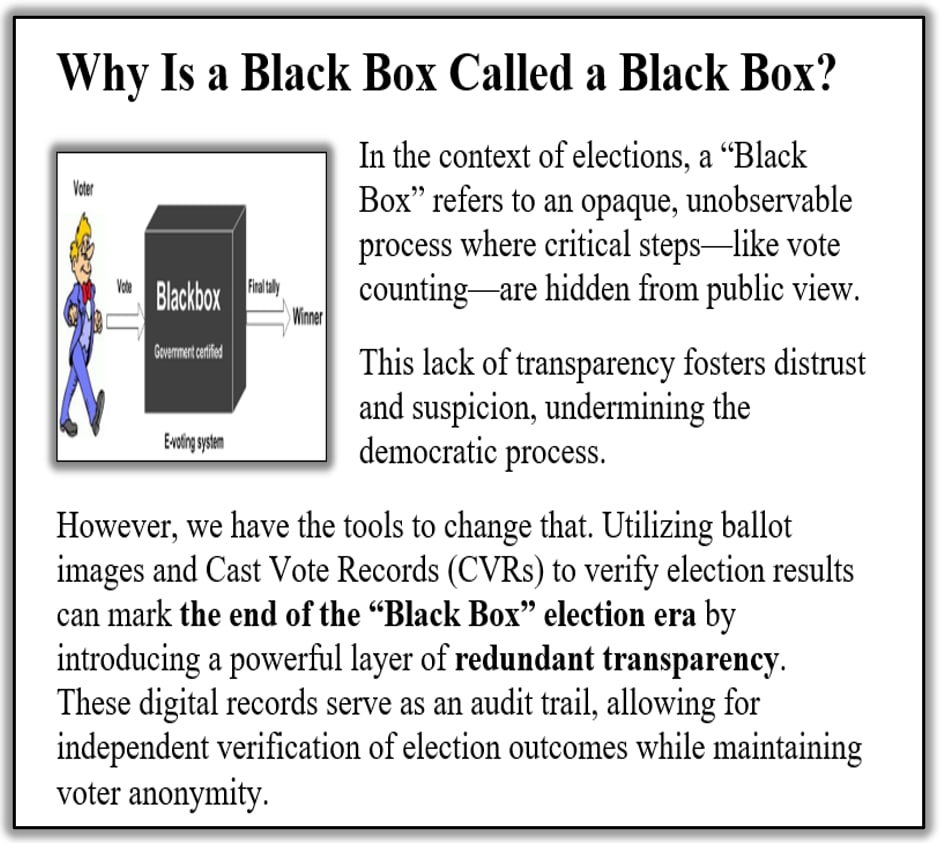

The lawsuit filed against AUDIT USA and me for requesting Cast Vote Records revealed more than a legal dispute; it exposed a deeper challenge in how civic transparency is sometimes treated when ordinary citizens ask lawful questions. When public-records requests are met with resistance rather than engagement, public trust is quietly weakened.

After the County’s position was rejected by the courts for a third time, Santa Cruz County issued a public statement asserting that it was acting to protect ballot anonymity—despite the fact that ballots, ballot images, and Cast Vote Records contain no voter-identifying information and cannot be used to determine how any individual voted.

More concerning was the County’s October 23, 2025 press release, which claimed that the Arizona Constitution guarantees voters the right to cast a ballot “free from identification, harassment, or retribution.” That principle is unquestionably important—but it does not appear in the Arizona Constitution in the manner suggested, nor has it been interpreted by the courts to prohibit public access to anonymized election records.

The County’s litigation relied on framing this claim as a constitutional requirement, even though that position has already been rejected in multiple court rulings. Presenting the issue in this way risks mischaracterizing both the law and the procedural history of the case, and it obscures the fact that the judiciary has repeatedly found no legal basis for withholding these records.

This matters not to assign blame, but to clarify the record. Transparency disputes should be resolved by reference to statutes, case law, and facts—not by assertions that imply constitutional barriers where none exist. Clear, accurate public explanations are essential if trust is to be restored and preserved.

Public Counting Protects Voters—It Does Not Expose Them

In practice, voter privacy is already overwhelmingly protected. More than 99.8% of every ballot is inherently anonymous, even when Cast Vote Records are disclosed. The remaining fraction—often cited to justify secrecy—can be addressed through simple, well-established safeguards that further protect anonymity without concealing the public record.

Privacy vs. Transparency: What a New Study Says About Releasing Ballots Authored By Rick Harrison March 12, 2025

Comparable safeguards are routinely used in public-interest data systems, including election administration, public health, and census reporting. Those safeguards are outlined below.

Invoking exaggerated privacy fears to justify secrecy does not protect voters. It misleads the public into believing transparency itself is a threat—when in fact, transparency is the mechanism that protects both voter privacy and public confidence.

The responsibility of public officials is not to defend machines or administrators. It is to defend the county itself—and the people who live here.

A Historical Parallel

In 1944, a man was blocked from speaking at a microphone. (Link to that story)

In Santa Cruz County today, public records are blocked instead—and citizens are met with a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation.

The method changed.

The lesson did not.

Inheritance Brings Duty

Neither of you created the conditions you inherited. But inheritance brings responsibility:

the duty to distinguish between privacy and verification,

the duty to ensure Arizona’s secrecy statutes are not used as shields for misconduct, and

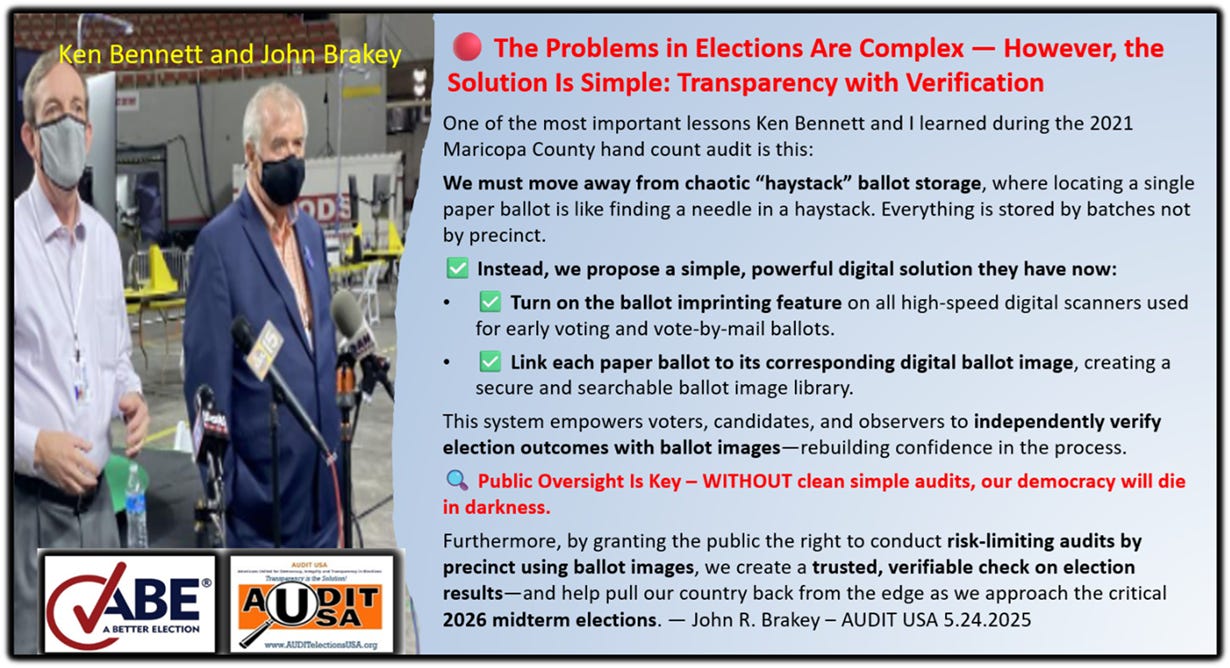

the duty to explore modern tools like ABE (Auditable Ballot Examination) that allow citizens to verify results offline, precinct by precinct, without touching a single official ballot.

That light can stabilize this county instead of dividing it.

Appreciation Before Accountability

Before any debate resumes, let me say this clearly:

Thank you for serving.

Democracy is repaired locally. Counties can lead the state instead of hiding inside it. If you choose transparency, the citizens of Santa Cruz County will meet you halfway—not with anger, but with courage and facts.

Santa Cruz County now stands at such a moment.

This letter is written to Supervisors Davis and Fanning—and to the citizens of Santa Cruz County—not as an accusation, but as a public record. It is written with respect, clarity, and a sense of urgency rooted in documented history.

For decades, Santa Cruz County has struggled with systemic failures in oversight, internal controls, and transparency. These failures were cumulative, not isolated—and they were enabled by a culture that discouraged scrutiny rather than welcoming it.

This letter exists for one reason:

Sunlight is the only remedy strong enough to restore trust.

What follows is not partisan.

It is structural.

It is documented.

And it is offered in the spirit of accountability—not blame.

Even the most capable public servants struggle under those conditions—not because of who they are, but because the environment pushes everyone toward caution, silence, and eventually groupthink.

“After more than 40 years working on transparency and accountability, I’ve learned how groupthink, gatekeeping, and institutional defensiveness take hold.”

Part I — The May 27, 2025 Meeting: A Case Study in Restricted Oversight

I observed this dynamic firsthand on May 27, 2025, when Supervisor Davis, Arlene Leaf, and I met. At the outset of that meeting, Deputy County Manager Chris Young instructed Supervisor Davis that “we are only here to listen.” That directive framed the entire interaction. It controlled the scope of discussion, limited meaningful dialogue, and effectively restricted Supervisor Davis’s ability to ask or answer questions.

As a result, Supervisor Davis was prevented from fully exercising his responsibilities as an elected official charged with investigating concerns and understanding how county operations function behind the scenes. The constraints placed on his participation limited access to essential facts and curtailed open inquiry.

This was not the conduct of a transparent system. It reflected an institutional posture that discourages candid discussion and resists scrutiny — particularly scrutiny that might reveal uncomfortable truths.

Effective oversight requires the ability to ask fundamental questions: who made a decision, what was done, and why.

Without that Transparency, meaningful accountability is impossible.

My hope is that we can move past this dynamic and work toward a healthier democratic culture — one grounded in openness rather than restriction.

Transparency is not a radical concept; it is a constitutional principle, rooted in the First Amendment’s protections of public access to government information and the people’s right to hold their institutions accountable.

Because that meeting raised serious concerns for me, I followed up with you, Supervisor Davis by email on June 4, 2025, and again over the days that followed. I was concerned that you may have been discouraged from engaging further on these issues.

For the sake of completeness and the public record, I have included a link to the full letter I initially sent to your home and later to your county office.

Part II — What Arizona Law Actually Requires of You

Most citizens don’t know what a county supervisor really does.

Most new supervisors don’t either — and that’s understandable.

Your Core Legal Duties — A.R.S. § 11-251

Under Arizona law, you are legally responsible for:

Supervising the official conduct of every county officer — including the Recorder, Treasurer, Elections Director, Assessor, and County Attorney.

Managing county finances, property, and administrative operations.

Ensuring lawful, properly conducted elections.

Investigating misconduct and correcting oversight failures.

Holding departments and officers accountable when performance breaks down.

These responsibilities are not optional.

They are mandated by law.

Your Authority to Increase Transparency A.R.S. § 11-251.05

This statute gives you broad power to adopt ordinances that exceed state minimum standards including:

Enhanced election-facility video surveillance

Strengthened chain-of-custody documentation

Clear, transparent observer rules

Independent public review and audit panels

Mandatory public reporting of election processes

You have more authority — and more responsibility — than most realize.

With that authority comes something else: the ability to fix what previous boards refused to confront.

Open Meeting Law Makes Your Job Even Harder (A.R.S. § 38-431)

On a three-member board:

Two supervisors talking privately = a quorum

You cannot compare notes, evaluate staff behavior together, or discuss county business outside of public meetings

Staff can talk to each of you individually.

You cannot talk to each other

This imbalance is exactly how long-time staff can maintain control of a county — even when voters elect new leadership.

I do not want that to happen to you, and I do not want it happening to the Citizen of Santa Cruz County.

This dynamic was on full display the day I met with Supervisor Davis. Staff controlled the meeting, dictated what could be discussed, and instructed him — in front of me — not to answer basic questions. That should concern every citizen.

A long-time Clerk and Elections Director who gave false testimony in court under oath in 2014 — documented through public records we finally obtained only after several months after the litigation.

A successor to Melinda Meeks Elections Director who, by many accounts, refused to “play the game” — and lost her position as a result.

A County Attorney’s Office that too often responds with intimidation rather than transparency, raising legitimate questions about missing funds and structural oversight failures and a sex scandal that cost the county $425,000

A Board of Supervisors that remained in place for 12–16 years, forming entrenched alliances with staff who had served even longer.

Part III — What You Inherited Was Not Your Fault

Santa Cruz County has endured a long-term breakdown in internal controls and oversight — the kind of systemic failure that accumulates over decades, not months. The record is not in dispute:

A $38 million embezzlement by the former County Treasurer — one of the largest fiduciary failures in Arizona history.

A theft involving the County Attorney’s anti-racketeering fund, still unfolding and now under active media scrutiny.

A former County Assessor convicted in a bribery and property-valuation corruption scheme.

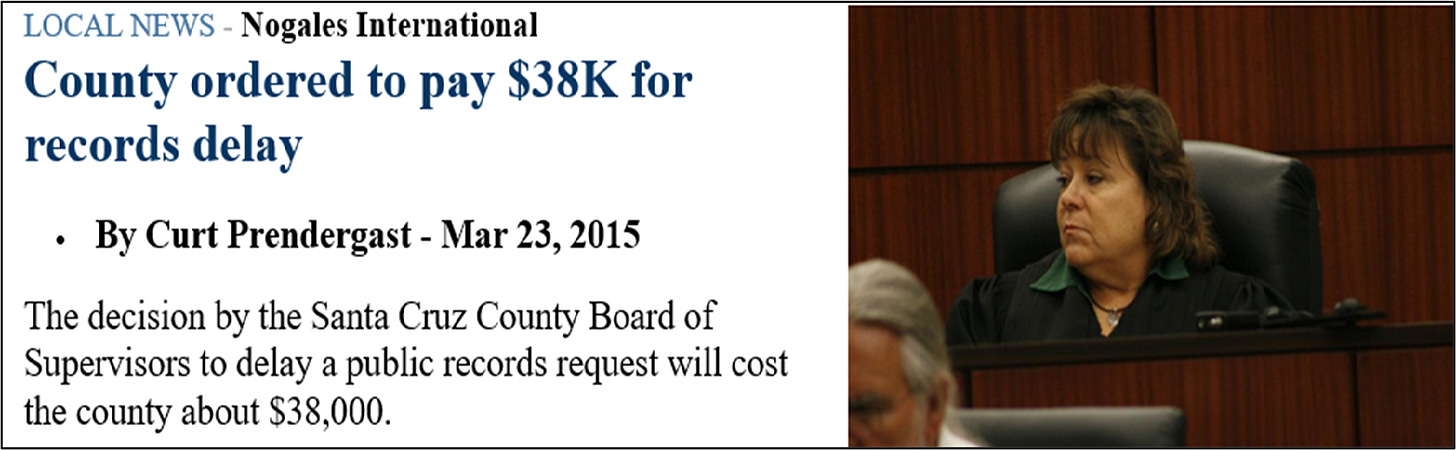

The County’s failure to provide public records to my organization in 2014, costing Santa Cruz taxpayers $38,000 when the County lost in court.

A long-time Clerk / Elections Director who gave false testimony in court under oath in 2014 — documented through public records we finally obtained only after several months after the litigation.

A successor to Melinda Meeks Elections Director who, by many accounts, refused to “play the game” — and lost her position as a result.

A County Attorney’s Office that too often responds with intimidation rather than transparency, raising legitimate questions about missing funds and structural oversight failures and a sex scandal that cost the county $425,000

A Board of Supervisors that remained in place for 12–16 years, forming entrenched alliances with staff who had served even longer.

Part IV —This is not a partisan critique.

This is structural corruption, and the informed residents of Santa Cruz County know it.

We must acknowledge another truth:

Everything is harder in a border county.

Santa Cruz operates at the intersection of:

Two cultures

Local, state, and federal jurisdictions

An international port of entry

Cross-border business and daily travel

A regional drug economy that attracts federal scrutiny, criminal networks, and political pressure

This complexity makes oversight more essential — not less.

And let me be absolutely clear:

Neither of you created these problems.

But the system that allowed them now sits on your desk.

If you are not careful, it will swallow you the same way it consumed prior boards.

You deserve a fair chance to lead — and the public deserves supervisors who understand exactly what Arizona law requires of you.

Historical Example: The 2014 Santa Cruz County Election-Programming Scandal

This is not the first time Santa Cruz County attempted to hide how its elections were run.

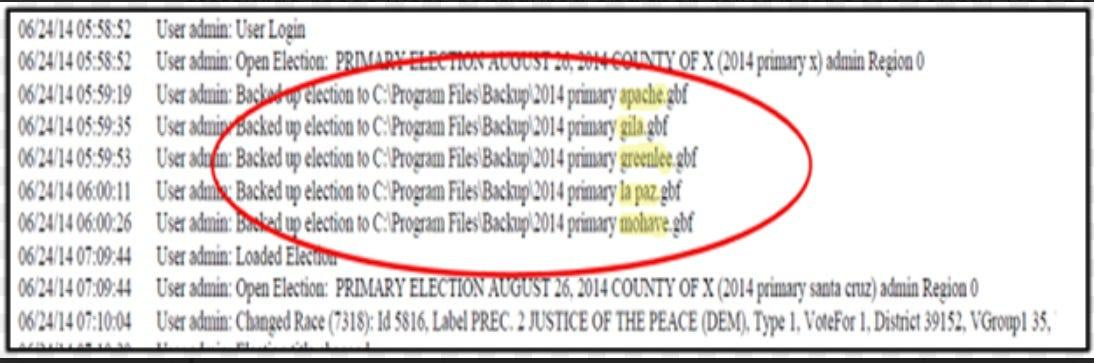

In 2014, during a public-records lawsuit, Elections Director Melinda Meek testified under oath that she personally programmed the county’s Diebold/GEMS system and that no outside vendor was involved.

After litigation, the election-system audit logs proved this testimony was false.

For years, election programming had actually been performed by William E. Doyle, a private contractor in Glendale who remotely accessed county systems using phone-modem lines — a practice prohibited under Arizona law due to its security risks.

Even more concerning, Doyle was quietly programming multiple counties statewide. Audit logs showed he built a statewide master database, then “forked” customized versions for Apache, Gila, Greenlee, La Paz, Mohave — and finally Santa Cruz, this came out of the Diebold audit log.

This pattern of concealed third-party involvement, prohibited remote access, and false testimony under oath revealed a deeper problem: institutional secrecy designed to prevent public scrutiny.

Part V — Why This Matters Today

This history helps explain the County’s extreme reaction to my July 28, 2022 public-records request.

I did not request the audit log in 2022 — ES&S uses a different system — but I did request:

the Cast Vote Record,

optional ballot images, (Per A.R.S 16-625 (Link to my Record Request)

three standard ES&S reports.

The first two of these records would have provided meaningful transparency into how the election was conducted.

Given what emerged in 2014, it is reasonable to infer that certain officials were concerned about what recent records might reveal. Their refusal to release CVRs, their decision to decline ballot-image disclosure (a right they possess under A.R.S. § 16-625), and their choice to file a SLAPP-style lawsuit instead of complying with routine statutory obligations all reflect the same secrecy exposed in 2014.

The transcript and video of Meek’s testimony — along with William E. Doyle: The Hidden De Facto Statewide Election Director and The Curious Business of William E. Doyle — are linked in Chapter 14.

What I Saw in 2022 at the Elections Department

When I visited in 2022, I found no evidence of manipulation within the Elections Department itself.

In fact, the operation looked significantly more professional than what I encountered in 2014.

I was particularly impressed with the professionalism of County Clerk / Elections Director Alma Schultz.

However, the same could not be said for the Recorder’s Office.

Part VI — A New Vulnerability: The Recorder’s Office and the Vote-By-Mail System

The greatest risk in 2022 came from the structure and practices overseen by then-Recorder Suzanne “Suzie” Sainz, who served for 27 years. Her mother had held the role before her.

Sainz operated a vote-by-mail system with virtually no oversight:

She maintained sole control over Vote by Mail (VBM) ballots — from receipt and signature verification to their transfer to the Elections Department.

In 2020, during her re-election campaign, she deployed external ballot-drop boxes at each precinct and personally retrieved the ballots without bipartisan observers, chain-of-custody documentation, or public visibility. She also encouraged voters not to mail their ballots but to use these drop boxes, which were set out weeks before the election.

This meant the public had no way to verify how these ballots were handled.

This structure created a situation ripe for abuse, even if wrongdoing could not be proven. It was a system built to conceal, not to reassure.

The 2020 Democratic primary results underscore how decisive this control was:

Sainz won by just 96 votes (3,275 to 3,179).

She significantly lost Election Day voting, where she had no control 514 to 357.

She lost provisional ballots — 16 to 9. (Links to sources of information: Nogales Int: source one, source two)

Her entire margin of victory came from the vote-by-mail process — a process she alone controlled.

In a race this close, process integrity is everything.

Control without oversight isn’t a safeguard — it’s an invitation to corruption.

My Direct Interaction with Sainz

This is where the story becomes personal and revealing.

At Voting Center #9 in Rio Rico, poll workers had placed a 75-foot electioneering boundary sign at 7:00 a.m. and removed it at 7:00 p.m.

When Sainz arrived to collect vote-by-mail ballots, she saw me standing outside the precinct. She immediately pulled a second 75-foot sign from her car and set it up — I photographed the sign at 7:29 p.m., after it had been taken down.

When I came within 10 feet to see what she was doing, she began shouting that I was violating state law.

I calmly explained that

the official sign had been removed at 7:00 p.m.,

the statute applies only between 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m., and

I was not engaging in political activity — I was observing, which the law permits.

Her reaction was not normal.

It was the reaction of someone operating a process that cannot withstand scrutiny.

Sainz knew I understood chain-of-custody requirements.

She also knew I had raised concerns about her VBM system. Whenever I asked a straightforward question, she insisted I file a formal records request.

In my opinion, Sainz may have contributed to provoking the 2022 lawsuit — possibly through false or exaggerated allegations — which then activated Supervisor Rudy Molera, and he activated Chief Deputy County Attorney Kim Hunley after finding another job she resigned and moved back to Tucson in September of 2024 and went to work for Pima county’s attorney’s office.

The most serious accusations made against me on election night came from Susie Sainz. Instead of addressing these claims under oath, Ms. Sainz resigned on December 22, 2022, shortly after the December 19 hearing, which Santa Cruz lost. The case was appealed twice more—both times unsuccessfully—resulting in three consecutive losses at taxpayers’ expense.

The Pattern Is Clear

Whether in 2014 or 2022, Santa Cruz County’s election vulnerabilities stem from the same root cause:

Systems controlled by individuals — without transparency, oversight, or accountability.

This is not sustainable.

And it is not compatible with public trust.

However, Sainz preferred to resign than have her unlawful VBM procedures exposed in court, and that’s what she did, resigning on December 22, 2022.

For the full investigative history of the 2014 case, see:

Chapter 14 — Investigative Reports 1, 2 & 3: “They Sued Us for Asking.”

Part VII — What Happened on Election Night — and Why It Matters to You

I wrote to Supervisor Davis afterward, and I am still awaiting a reply.

(Link to letter from June 4th.)

Supervisors, I recount these events not to reopen old wounds, but because they reveal the culture of intimidation and misinformation that existed before you took office — and why it must never return. These events from the August 2, 2022 primary election are part of the documented public record, witnessed by multiple individuals, and directly relevant to understanding how Santa Cruz County reached its current crisis of trust.

I have monitored elections statewide since 2006. I know the difference between routine procedures, human error, and coordinated obstruction. What happened that night was not routine.

The Factual Sequence of Events

1) The short version

On August 2, 2022, county staff and legal officials engaged in actions that appeared coordinated, retaliatory, and designed to suppress lawful election observation.

2) The underlying motive

I had previously prevailed in a 2014 public-records lawsuit that required the county to pay $38,000 in attorney’s fees. My involvement was resented by certain officials.

This 2022 incident bears the hallmarks of a retaliatory SLAPP action — an attempt to intimidate.

3) Lingering hostility

Some long-time officials remained openly hostile toward my continued election-transparency work eight years after the ruling — a clear sign of how entrenched the old culture had become.

4) Election night events begin

On election night during the August 2, 2022 primary, then-Supervisor Rudy Molera appeared to influence interactions involving me and Chief Deputy County Attorney Kim Hunley. Hunley repeatedly stepped into the County Attorney’s Office adjacent to the Elections Department, made a series of phone calls, and each time returned more tense and agitated.

5) The turning point

After I took three photographs documenting sealed ballot bags — which is lawful under Arizona public-records principles and ACLU guidance — Hunley went back into the office again. Minutes later, she emerged visibly escalated, flanked by two Sheriff’s deputies, and ordered me to delete the photos “or else.”

6) Why the photographs mattered

I photographed these sealed ballot bags to document the integrity of the transfer process. I am familiar with these seals statewide and can attest to their quality. My purpose was transparency, not confrontation.

7) Before the escalation

Up to that moment, she and I had been interacting professionally and without conflict. The sudden shift in tone and posture was striking — and consistent with someone acting under direction.

8) The larger pattern

What followed appeared to be a coordinated attempt by county staff to provoke, discredit, remove, or possibly arrest me — all for doing nothing more than lawfully observing a public election process. According to ACLU guidance, photographing or recording what is plainly visible in a public space, including government officials performing their duties, is a protected constitutional right.

Part VIII —Why This Should Matter to You

This was not an isolated incident.

It was a symptom of a system that:

weaponized staff authority,

punished transparency,

retaliated against oversight, and

used law enforcement to shield misconduct instead of correcting it.

Your challenge — and your opportunity — is to ensure this culture never returns!

What Happened at Central Count

When I arrived at Election Central Count on August 2, 2022, Chief Deputy County Attorney Kim Hunley approached me, confirmed my name, and we had a professional, uneventful conversation for roughly 30 minutes. Throughout that time, she repeatedly stepped into the adjacent County Attorney’s Office, evidently reporting to someone.

After I took three lawful photographs in the public hallway, she went back into that office again. When she returned, her demeanor had changed abruptly. She called over two Sheriff’s deputies and—despite no posted prohibition in that area—ordered me to delete the images “or else.”

The reaction made no sense. I calmly explained that Arizona law (A.R.S. § 16-621(D)) requires live video coverage inside the tabulation room, streamed both to the public and to the Secretary of State. In other words:

The most secure area in the building—the tabulation room—was already under continuous livestream surveillance.

What I photographed outside the tabulation room involved no privacy issue, or security issue, and violated no statute against.

Nevertheless, to avoid escalation, I fully complied. Hunley personally reviewed each image, instructed me to delete, and permitted me to retain only the photograph documenting that ballot bags were properly sealed.

A few minutes later—despite my cooperation—Hunley asserted that I was “not authorized” to be present, even though:

I had been explicitly invited by Elections Director Alma Schultz.

A.R.S. § 16-621(A) clearly permits public observation of Central Count.

The posted “no photography” signs applied only to early voting, not to Central Count, and staff were fully aware of that distinction.

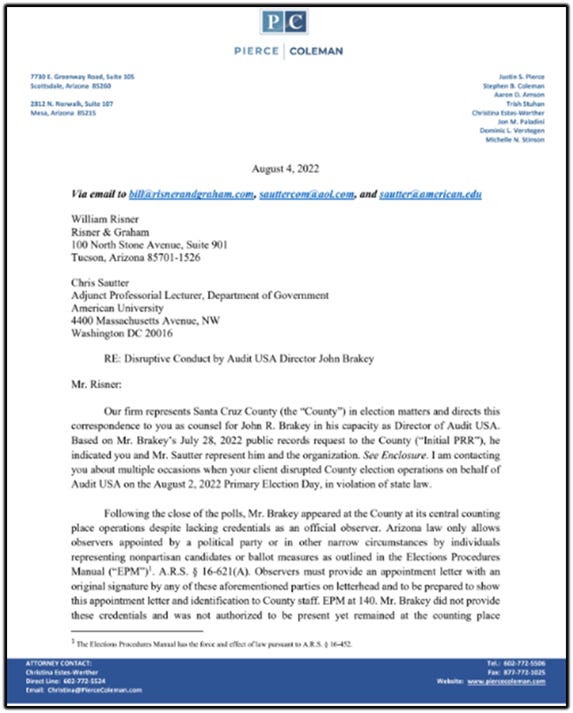

Shortly afterward, Pierce Coleman law firm sent a letter on August 4, 2022 to my attorneys alleging misconduct on my part that evening.

In response, attorney Bill Risner and I filed multiple public-records requests seeking any documentation supporting those claims.

The county’s reply was they had no documentations, 3 the cameras in the hallways were not working and there was no incident report filed with the Sheriff’s Department. However they stated they stand by the August 4, letter.

Part IX — The Confrontation That Followed — and What Happened at the Holiday Inn

After the incident at Central Count, I met with several candidates—including former mayor John Doyle and mayor-elect Jorge Maldonado—at the Holiday Inn to debrief and discuss the events of the evening.

Within approximately five minutes of my arrival, Supervisor Rudy Molera entered the room. He appeared visibly agitated and unkempt, and I did not immediately recognize him. Multiple witnesses observed him walk directly toward me with clear purpose.

When he reached me, Supervisor Molera confronted me aggressively. He raised his voice, moved into my personal space, and expressed anger regarding the county’s 2014 public-records litigation—a case the county lost, resulting in a court order requiring payment of my attorney fees. He accused me of “causing trouble” simply by being present that night as a lawful public observer.

His conduct was intimidating and disproportionate to the circumstances. Based on the manner of his approach, the timing of his arrival, and the tone of the confrontation, it reasonably appeared intended to provoke a reaction.

Earlier that evening, Deputy County Attorney Kim Hunley had made a series of phone calls during and after my interaction with her at Central Count. Given the sequence of events, it is reasonable to conclude that Supervisor Molera had been alerted. When earlier efforts through county staff failed to deter or intimidate me, the situation appeared to shift from administrative pressure to personal escalation.

I did not respond in kind.

I did not raise my voice, argue, or engage. Years ago, I learned through experience that escalation rarely serves the truth. Civility, restraint, and clarity are not signs of weakness; they are how credibility is preserved.

In that moment, I reflected on what I call my Seven C’s: Character, Capacity, Credibility, Civility, Citizenship, Country, and Courage. These principles guide both my work and my life, and they underpin more than two decades of advocacy for transparent, trackable, publicly verified elections.

After a brief exchange, I simply said goodnight to my friends and left.

A Pattern of Escalation and Retaliation

The cumulative effect of that evening was significant.

The first escalation occurred at Central Count, where I was threatened with arrest for refusing to delete lawful photographs taken in a public space. The second occurred later at the Holiday Inn, when a county supervisor confronted me in an aggressive and intimidating manner.

Both incidents were witnessed by others.

Former mayor John Doyle told me immediately afterward that Supervisor Molera had a reputation for bullying behavior and that he had personally observed similar conduct in the past.

These incidents were deeply inappropriate. Together, they reflect a broader pattern in Santa Cruz County in which lawful observers and public-records requesters are treated not as citizens exercising protected rights, but as adversaries to be discouraged.

History shows that when authority responds to scrutiny with escalation rather than transparency, outcomes can spiral in ways no one intends. I am acutely aware of this reality. It is precisely why I remain committed to de-escalation, restraint, and lawful process—even when confronted with hostility.

Why the County Filed Suit in Pima County

It is notable that Santa Cruz County did not file its lawsuit against me in Santa Cruz County Superior Court. That court—and its elected judges—are familiar with the county’s public-records litigation history, including prior cases in which the county’s legal position was rejected (see Chapter 14.)

Instead, the county filed suit in Pima County Superior Court, where judges are appointed and later stand only for retention. This strategic decision strongly suggests forum shopping designed to obtain a more favorable venue.

At the first hearing in Pima County, the judge immediately questioned the case, asking in substance:

Why is this case in my courtroom? Why isn’t this in Santa Cruz County? And why is the county suing a public-records requester? Mr. Brakey has the right to request these records. Your obligation is to provide them or cite a statutory reason for denial.

The case was dismissed.

Despite this, the county appealed—without new facts or legal grounds—and proceeded to lose repeatedly. To date, this litigation has cost Santa Cruz County taxpayers well over $100,000, with costs continuing to rise. Additional examples of similar failed litigation by county counsel aappear in Chapter 14.

As the judge made clear, the law already provides a straightforward process: if a requester is dissatisfied with a denial, the requester may seek judicial review. Suing the requester instead reverses that process entirely, Escalating the cost of the litigation dramatically.

What was a simple case if I was to file would be about the statutory reason they used and was it valid or not. Not all the other crap they pulled into the case. The only people who win thus far in this case is the private lawyers.

The pattern is unmistakable.

This case fits the definition of a SLAPP lawsuit—a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation—designed not to prevail on the merits, but to intimidate, punish, and discourage lawful public oversight.

A Dangerous Adrenaline Crash After the Confrontation

When I left the Holiday Inn, the confrontation had ended—but its physical effects had not.

The combined stress of being threatened with arrest at Central Count and then aggressively confronted by a county supervisor triggered a severe adrenaline response followed by a dangerous physiological crash.

As I drove away, my hands trembled on the steering wheel. My breathing became shallow. My vision began to distort and tilt. I recognized these warning signs immediately. Two years earlier, following a similar high-stress incident, I had blacked out, fallen, and suffered a serious head injury requiring hospitalization.

Knowing the risk, I pulled off the highway and parked on the shoulder in the dark. For nearly an hour, I focused on slow breathing, waiting for my nervous system to stabilize before continuing home.

Anyone who has experienced an adrenaline crash understands that trauma does not end when an encounter ends. It lingers in the body. It is a hidden but very real cost of confronting entrenched systems of power—and it should never result from simply observing a public election or requesting public records.

Every escalation that night—every hostile action and every physical consequence—traced back to something entirely ordinary and lawful: a routine public-records request submitted on July 28, 2022.

Yet lingering resentment over our successful 2014 litigation, combined with resistance to election transparency, led Santa Cruz County to take an extraordinary step.

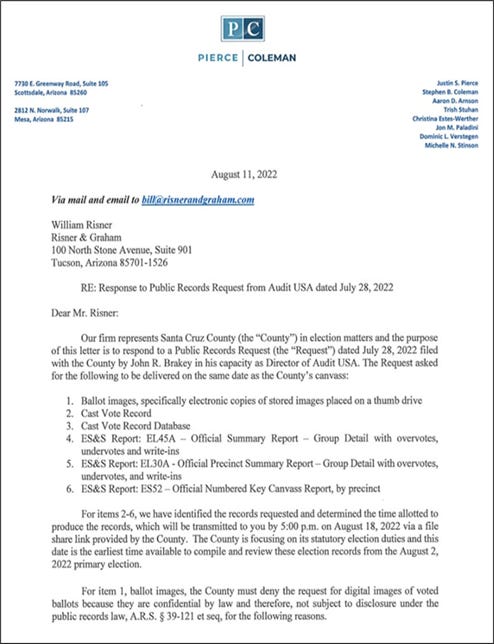

On August 18, 2022, the county filed a lawsuit against me and AUDIT USA solely for requesting the Cast Vote Record (CVR)—a standard election record the county had previously provided without objection.

What makes this filing particularly troubling is the record the county itself created.

On August 11, 2022, the county sent a written letter stating that it would provide the requested records no later than August 18, 2022. That is the very same day the lawsuit was filed.

Subsequently, in filings submitted to the court, the county did not disclose that commitment. Instead, it represented that the records were still being processed and that the county might provide them during the week of August 15.

These two positions cannot both be true.

One document represents a firm commitment to production by August 18. The later court filing introduces uncertainty and omits the prior written assurance. That inconsistency is material. It deprived the court of a complete and accurate picture of the county’s own representations and undermined the premise for filing suit at all.

This contradiction is not a matter of interpretation. It is documented. And it goes to the heart of why this lawsuit should never have been filed in the first place.

Part X — The SLAPP Lawsuit Filed by Santa Cruz County

The lawsuit filed against me and AUDIT USA by Santa Cruz County exhibited the defining characteristics of a SLAPP lawsuit—a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation—intended to deter lawful oversight and discourage citizens from exercising their public-records rights.

Specifically, the lawsuit:

Contradicted the county’s own prior public-records practices

Singled me out, even though others had requested the same record

Lacked legal basis, as later recognized by both the Superior Court and the Court of Appeals

Cost Santa Cruz County taxpayers well over $100,000 in outside legal fees

Continues to expose taxpayers to an additional $57,000 in potential liability on top of the $20,000 that has already been awarded but not yet paid.

My request for records did not justify such an extraordinary response. My conduct on election night was lawful, non-disruptive, and consistent with long-standing public-records and election-observation principles. There was no legitimate basis for threats, escalation, or litigation.

Only later did I learn that the county was also under federal scrutiny related to the County Assessor’s bribery case. Around the same time, serious questions were emerging regarding the County Treasurer’s case, including issues raised publicly by the Arizona Auditor General. I attended one of the two court hearings related to those matters and was struck by how much of the process appeared to unfold outside public view.

In that context, Santa Cruz County retained Snell & Wilmer, one of the nation’s 109 largest and most influential law firms, with extensive experience representing government entities in complex, high-exposure matters.

Their involvement was not improper; large firms are often engaged when legal, financial, and political stakes are high. However, the result was a process that became increasingly opaque to the public, reinforcing the perception that transparency was being managed rather than embraced again.

At that moment in Santa Cruz County, transparency was treated not as a public right, but as a liability to be controlled.

Part XI — Why Transparency Protects You — Not Just the Public

Supervisors Davis and Fanning, let me put this plainly:

Transparency is your shield.

Secrecy is your liability.

For decades, the people of Santa Cruz County have endured:

Cover-ups

Hidden financial failures

False accusations designed to silence critics

Illegal election programming conducted over unsecured phone lines (see Chapter 14)

Long-time staff who manipulate or mislead newly elected officials

You did not create these conditions — but you inherited them. And now the public will look to you to fix them.

When you sit in the supervisor’s chair, fair or unfair, the public no longer cares who caused the mess — only whether you clean it up.

That is why transparency is not merely “good government.”

It is self-protection.

When everything is in the open:

No one can use you to hide wrongdoing.

No one can mislead you behind closed doors.

No one can blame you for decisions you never made.

No staff member can manipulate what you know — or don’t know.

No one can weaponize secrecy to turn the public against you.

Yes, sunlight protects the public — but it also protects you

If you want to rebuild trust in Santa Cruz County, transparency cannot be an occasional gesture. It must become the default, the culture, and the expectation.

Not just for elections — but for every department that handles public money, public records, or public power.

You are stepping into a battlefield you did not choose.

But you will be held responsible for the outcome.

And in this environment, there is only one shield that works:

radical transparency.

Part XII — A Path Forward: A Santa Cruz County Transparency & Elections Oversight Commission

Santa Cruz County cannot continue operating in a system where information is filtered, oversight is symbolic, and staff can play supervisors against each other by controlling the flow of information and facts.

The $38 million embezzlement, falsified financial reports, election-night misconduct, and years of ignored internal-control warnings all point to one truth. This is what happens when internal controls fail and everything is done in the dark.

The solution is structural. A permanent Transparency & Elections Oversight Commission gives the Board a public, lawful forum to oversee elections, finances, and public-records practices — and it allows Supervisors Davis and Fanning to communicate openly under the protections of the Open Meeting Law.

Instead of being isolated and manipulated individually, they can compare notes, see the same data, ask the same questions, and take action together. This is how you break the cycle — and how you prevent staff from dividing and conquering newly elected supervisors.

This is how you break the cycle — and how you prevent staff from dividing and conquering newly elected supervisors.

Establishing this Commission is legal under Arizona law.

Commission Structure (9 Members)

A nine-member design ensures balance, credibility, and independence.

Four Board-Connected Seats

One appointee per Supervisor (they may appoint themselves).

The Clerk of the Board/Elections Director — or a designee — serving as a non-voting procedural advisor.

This guarantees Board participation while preventing staff from dominating oversight.

Five Public Voting Seats (One from Each Party)

To ensure independence and broad legitimacy, five seats must be filled by citizens representing the county’s political diversity:

Republican – appointed by county party chair

Democrat – appointed by county party chair

Independent – 10 signatures from registered independents

Libertarian – 10 signatures or state chair appointment

Green Party – 10 signatures or state chair appointment

No party can dominate. No faction can control. Independence is built into the structure.

Commission Powers

Under full Open Meeting Law compliance, the Commission will:

Oversee elections, chain of custody, ballot images, CVRs, and audits

Ensure compliance with A.R.S. § 16-621 (live video and public observation)

Monitor public-records practices and identify obstruction or retaliation

Review Auditor General findings and strengthen internal controls

Receive whistleblower information and request documents

Publish quarterly and annual transparency reports

This creates a continuous oversight mechanism rather than responding to crises after they erupt.

Why This Matters

If nothing changes, the county will continue operating in the dark — and staff will retain the ability to mislead, isolate, and manipulate elected officials. However, if you adopt this Commission with independence and teeth, you create the first real system of transparency in Santa Cruz County history. It protects taxpayers, protects supervisors, and restores public trust.

Most importantly, it provides Supervisors Davis and Fanning with an opportunity to collaborate in a lawful and transparent manner to address longstanding issues.

Because this Commission may become the single most important tool you have for restoring trust — and for preventing staff from isolating or misleading you. I strongly encourage you to review the full proposal. It includes the legal authority, structure, and safeguards necessary to make this Commission effective and independent.

The complete version is available here:

Full Transparency & Elections Oversight Commission Proposal is Hyperlink— and to the Community

Supervisors Davis and Fanning, let me make something absolutely clear:

I am not your enemy.

I am not here to embarrass you.

I am not here to ask for special treatment.

I am speaking up because I believe in the people of Santa Cruz County — and because I believe you have the potential to break a cycle that has held this county back for decades.

My goals are simple:

I want you to succeed.

I want Santa Cruz County to rise above its history.

I want you to be remembered — not as another Board swallowed by secrecy,

but as the Board that finally ended the culture of concealment.

If you choose transparency and accountability, the public will stand with you. You will gain:

Credibility

Trust

A legacy worth defending

If you do not, the old system — the one that operated long before you arrived — will do what it has always done. It will:

Blame you

Isolate you

Undermine your work

Erode your credibility

The stakes are real, but so is the opportunity.

You can lead this community forward together — with truth, compassion, firmness, and courage.

My commitment is simple:

I will work with you, not against you, to help build a culture of transparency that protects both the public and the Board.

This is not an adversary’s message.

This is an invitation — for partnership, for reform, and for restoring trust in Santa Cruz County.

Part XIII - To the People of Santa Cruz County

The people of Santa Cruz County deserve a government that:

Tells the truth

Welcomes oversight

Respects the law

Treats citizens as partners, not obstacles

Understands that democracy cannot function in the dark

Supervisors Davis and Fanning did not create these problems.

But they now hold the responsibility — and the authority — to fix them.

To succeed, they need support.

They also need to raise their expectations — of themselves, of county staff, and of every process that touches public trust.

Accountability and empathy are not opposites.

In healthy government, they walk together.

Let us demand transparency — not as punishment, but as the foundation for rebuilding trust. With support, cooperation, and honest dialogue, this Board can fix what has been broken. You can rebuild a county government worthy of the people who live here.

Santa Cruz County has been bankrupt in transparency for far too long.

It is time to restore what was lost.

It is time to bring sunlight back into public life.

The stakes are real, but so is the opportunity.

You can lead this community forward together — with truth, compassion, firmness, and courage.

My commitment is simple:

I will work with you, not against you, to help build a culture of transparency that protects both the public and the Board.

Part XIV - Final Chapter: A Reasonable Path Forward — and the Consequences of Refusal

Notice Regarding Federal Civil-Rights Remedies (42 U.S.C. §1983)

Supervisors Davis and Fleming,

I want to be clear about my intent and my values.

My goal is not to punish Santa Cruz County. My goal is to help the County correct a long-standing culture of concealment, retaliation, and avoidable conflict—particularly where elections and public records are concerned. I am acting in good faith, with respect for this community, and with a sincere desire to restore public trust.

I would much rather help build durable reform than spend the next phase of my life in court.

However, at this point, the County’s legal exposure is no longer theoretical.

Notice of Federal Civil-Rights Liability

Beginning on August 2, 2022, and continuing to the present, I have been subjected to a sustained pattern of obstruction, retaliation, and denial of lawful access to public election records. These actions were undertaken by individuals acting under color of state law, including county officials and legal representatives.

Federal statute 42 U.S.C. §1983 exists to protect citizens when government actors violate constitutional rights. To prevail under this statute, a plaintiff must show:

That a constitutional right was violated; and

That the violation was committed by persons acting under color of law.

The record assembled in this report, along with supporting documentation, demonstrates evidence of:

Retaliatory litigation and intimidation intended to chill protected First Amendment activity;

Bad-faith conduct inconsistent with constitutional and statutory obligations;

Misuse of public resources to suppress transparency, accountability, and lawful oversight.

Litigation and intimidation are not governance. They are liabilities.

I want to emphasize this clearly: a lawsuit is not my preferred tool. It is my last resort.

This is not a threat. It is notice—grounded in law, evidence, and the ongoing obligation of government to respect constitutional limits.

A Good-Faith Path Forward

I continue to seek resolution without litigation, through reform, accountability, and cooperation. What I am asking for is practical, responsible, and achievable:

1. Close This Conflict

Good-faith resolution of pending disputes

An end to retaliatory posture and unnecessary escalation

2. Make the County Whole by Doing the Right Thing

Payment of reasonable attorney fees and costs incurred as a direct result of this conflict

Reimbursement of documented economic harm, including lost wages and measurable fundraising impact caused by the County’s litigation and conduct

3. Build Structural Transparency Going Forward

Establish an Election Transparency Commission by Board action

Publicly adopt clear standards and timelines for election-related public records and citizen oversight

4. Implement Reform with Competence and Continuity

Appoint me as non-voting Executive Director for an initial 18-month implementation period, to help the County build a modern, lawful, and transparent election system

Compensation of $3,000–$4,000 per month, reflecting the level of effort and expertise required

A written deliverable at the conclusion of the 18 months: a public report, updated policies, and a sustainable transparency framework

This proposal is not self-serving. It is solution-oriented. It is designed to protect the County, serve the community, and restore confidence in our democratic processes.

If the County Declines - This Off-Ramp

If these reasonable steps are refused, and the documented conduct persists, I will have no choice but to protect my rights—and the public interest—through legal avenues. This may include pursuing federal civil-rights remedies under 42 U.S.C. §1983, where the record supports claims that government actors, acting under color of law, took adverse action in response to protected activity and caused economic, reputational, and emotional harm.

No one benefits from that outcome—not the County, not the community, and not the public servants who are trying to do the right thing today.

That is why I am asking you to act now.

The Decision Point

This is the moment to choose:

Reform and resolution, with transparency as the guiding principle; or

Continued escalation, increased liability exposure, and deeper public mistrust.

I am still offering to help Santa Cruz County move forward with dignity, legality, and credibility. I am offering a solution that is workable, realistic, and grounded in good faith.

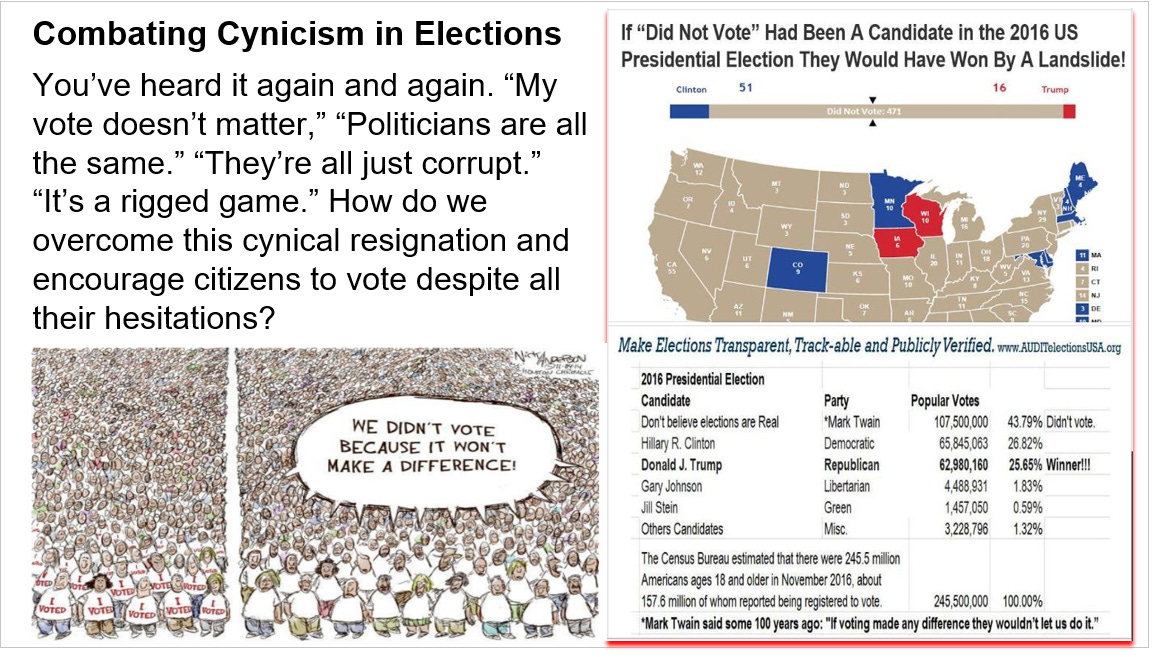

Too many people in this country have given up on voting because they no longer trust the system. We are approaching a dangerous crossroads—ballots or bullets. I stand firmly for ballots, with transparency, so elections can once again prove themselves to the people.

Transparency is the currency of trust.

And trust, once lost, must be rebuilt with action—not words.

With hope, and with a fierce commitment to a healthy Democratic Republic with verified elections.

John R. Brakey

Executive Director, AUDIT Elections USA

Co-Developer of the ABE Hybrid Verification System

Election Transparency Investigator, Educator & Reform Advocate

📞 520-339-2696

JohnBrakey@gmail.com

ABE Video Demo by Ellen Theisen 19 minutes)

Link to this story on John Brakey Substack: https://johnrbrakey.substack.com/p/they-sued-us-for-asking-inside-santa

AUDIT USA Launches Free Election Verification Tool ‘ABE’ By Jonathan Simon This tool promotes election integrity by providing evidence-based transparency, potentially curbing misinformation related to election fraud.